Recent

Section 106 is a major part of the national historic preservation ecosystem.

Summer 2025 is winding down, in terms of months if not the temperature.

At an intersection of Washington Street and Massachusetts Avenue, where South End meets Roxbury, stands Hotel Alexandra, an adorned, five-story High Victorian Gothic building.

James is a Landscape Architect at the National Park Service, where he specializes in design, planning, and management of cultural landscapes as part of the Olmsted Center for Landscape…

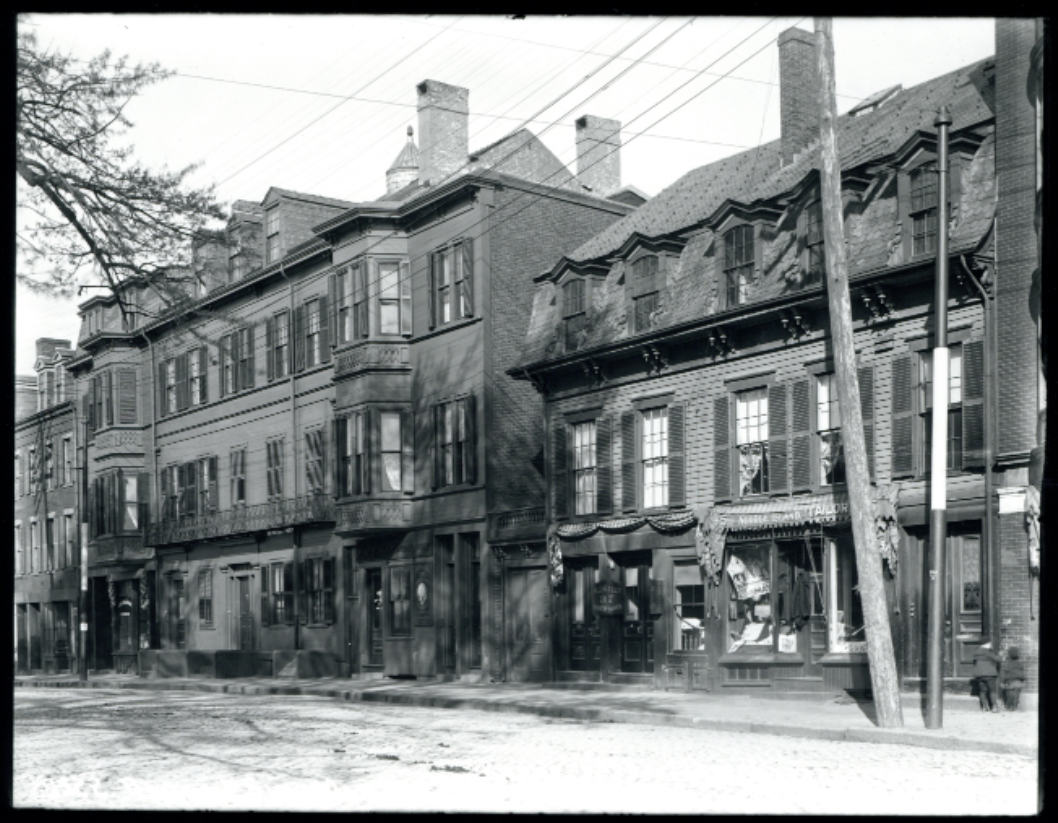

In the early 1840s, on a street off Boston Common now known as the Ladder Blocks, a modest brick federal row house at 13–15 West Street became a center of radical thought.

Flow Forward: A Night at the Waterworks Museum

When: May 20, 2025

Where: Waterworks Museum

Time: 6pm

Award recipients will be announced in late May.

Each year the Boston Preservation Alliance presents the Preservation Achievement Awards to recognize a group of exemplary…

This spring the Boston Preservation Alliance is partnering with Boston By Foot (BBF) to present walking tours…

“Love is showing the important things that they matter.” A Heart-bombing quote from the Frederick Pilot Middle School.

There was a newspaper clipping tacked to the wall in our office when I first joined the Alliance in 2013.

In partnership with the Dorchester Historical Society and Comfort Kitchen.

When: Sunday, October 20, 2024

Time: 2:30pm - 6:00pm

The City of Boston, with strong support from the Wu Administration, is advancing a proposal to…

Boston Preservation Alliance Presents their 36th Annual Achievement Award Recipients

Welcome to the third Alison About Boston blog post! I am the Executive Director of the Boston Preservation Alliance, which means that I wear many hats including leading our advocacy…

Welcome to the second Alison About Boston blog post! I am the Executive Director of the Boston Preservation Alliance, which means that I wear many hats including leading our advocacy…

When: May 9

Time: 4:30-6:00pm

Meeting Point: The Grain Exchange Building, 177 Milk Street

Register by emailing mdickey@bostonpreservation.org.

Welcome to the first Alison About Boston blog post! I am the Executive Director of the Boston Preservation Alliance, which means that I wear many hats including leading our advocacy…

May is National Preservation Month, giving us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

Several new Landmarks have been designated in Boston. Even more are pending approval and awaiting community feedback and support.

“Love is showing the important things that they matter.” A Landmark Love quote from the Frederick Middle School.

Update: February 29, 2024

The Boston Preservation Alliance has submitted a letter to the Wu Administration.

A Visual Guide to “Barbitecture” and Real-life Doll Houses

Written by: Sara Brown

Alliance Executive Director Alison Frazee received a call last night from Mike Firestone, the City’s Chief of Policy, informing her that the Landmarks Commission has been…

May is National Preservation Month which gives us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

May is National Preservation Month which gives us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

On behalf of the Boston Preservation Alliance and Boston’s preservation community, we would like to thank Councilor Kenzie Bok for her dedication to our city’s historic resources.

The Codman Award for lifetime achievement, named for John Codman who established Boston’s first historic district (Beacon Hill) in 1955, recognizes outstanding and career-long…

Thank you for helping us redefine preservation. Architecture is the surface of a city, but our history is deeper than a facade. It is the people, residents, and visitors that make Boston…

The leaves have been shaken off the trees, there is a chill in the air, and the sun sets just after 4 pm–that’s right, it’s nearly winter in New England and the gift-giving…

Written by Anan Shen. This is the first of a series of short stories about the West End.

As an advocacy organization for historic preservation, the Alliance often advocates to save historic buildings because of their stunning architecture or articulated streetscape.

Stories about our neighborhoods are often told by adults for adults. But what landmarks and businesses define our neighborhoods through the eyes of the next generation?

Thousands and thousands of buildings line Boston’s streets. But one house is different from all the rest. It takes a bit of determination to find it.

Photos by Peter Vanderwarker.

A Weekend Photo Workshop with Peter Vanderwarker, Sept. 16-18

May is National Preservation Month which gives us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

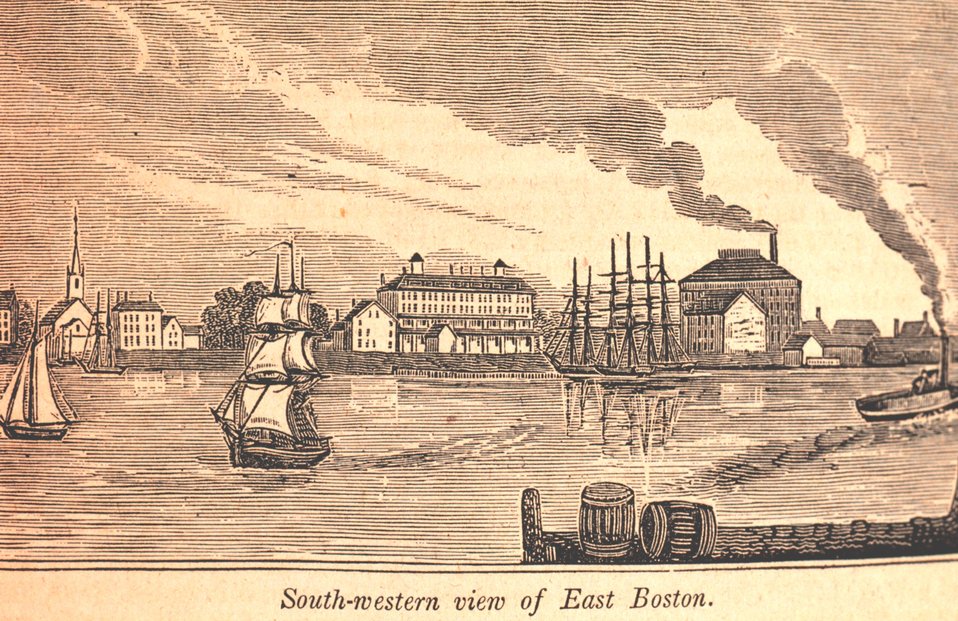

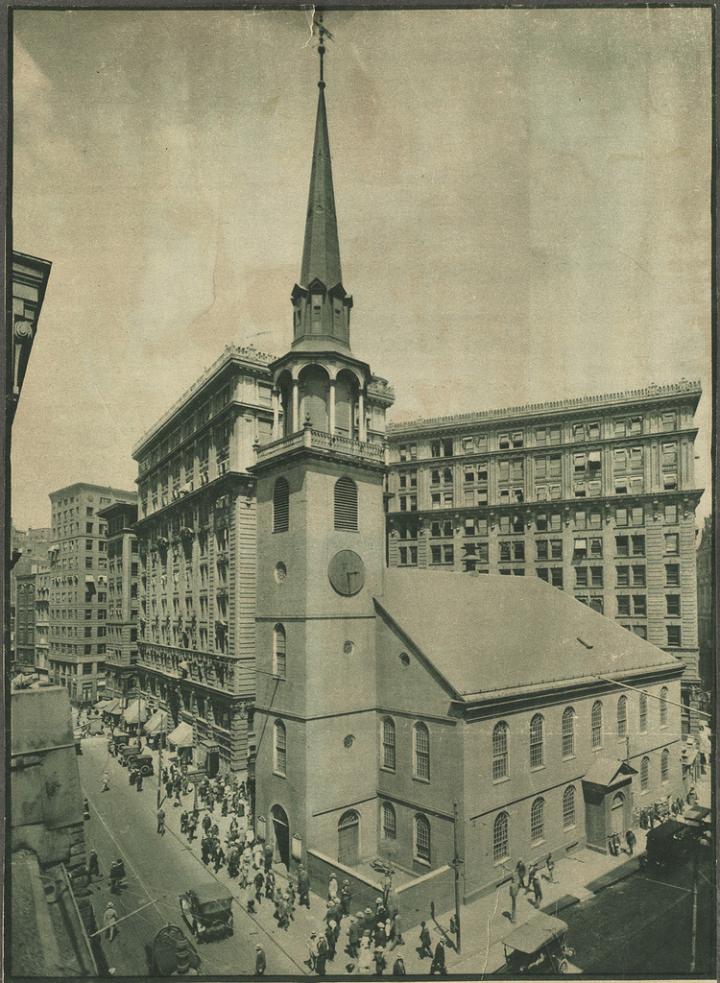

On May 1, 2022, Boston celebrated the 200th anniversary of incorporation as a city at the Old South Meeting House.

Valentine’s Day is approaching and that means only one thing—it’s time to dust off those markers and share some love (Heart Bombs) for old buildings! What are heart bombs?

In a little triangle just south of Andrew Station, Polish and American flags fly in pairs. The air wafts with the smell of freshly fried dough.

Our Most-Watched Advocacy Projects of 2021 Are Below, But First…

The Alliance relies on generous supporters like you to continue our work in promoting, preserving,…

The Alliance has been utilizing every opportunity to further our goals of historic preservation advocacy and telling the fuller story of Boston’s past. Below are a few of our 2021…

Thursday, December 2, 10:00-11:00 am.

The Boston Preservation Alliance is Boston’s primary, non-profit advocacy organization that protects and promotes the use of historic buildings and landscapes in all of Boston’s…

Turn on your favorite sea shanty and prepare for the water. The Young Advisors are bringing their annual Libations for Preservation event to the sea!

Written by Ava Yokanovich

Photos by Ava Yokanovich

Interview with Angela Ward Hyatt

Photos courtesy of Angela Ward Hyatt

Before and after photos below!

Memories from former South End residents Judith Nee and Isabel O’Hara

Images from Neil Kadey and Judith Nee

Written by Judith Nee and Ava Yokanovich

Written by Mackenzie Barrall and Corinne Muller. Photos by Matthew Dickey.

Originally published July 2020. Updated July 2021.

The Alliance works closely with the Boston Landmarks Commission (BLC), which resides within the Environment Department at the City, to further preservation efforts in Boston.

Written by Mackenzie Barrall

Photos by Ava Yokanovich

Written by Ava Yokanovich

Images taken by Ava Yokanovich along the Southwest Corridor Path near Titus Sparrow Park

Since 1988, the National Trust has used its list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places…

Since 1988, the National Trust has used its list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places…

Since 1988, the National Trust has used its list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places…

Written by Jeanne Pelletier, Preservation Advisor to the Campaign for the Ayer Mansion, Inc.

There are untold stories in Boston being lost and we need your help to save them.

Save-The-Date

When: March 25

Time: 6 pm via Zoom

Featuring: Brent Leggs

This event is generously supported by the Nolan-Miller Fund

Corita Kent (1918–1986)

Artist, Educator, Advocate for Social Justice

Written by: Vicki Adjami

When: March 4

Time: 10 AM

Where: On Zoom

How: Register below to receive a zoom link

The Boston Preservation Alliance and the Young Advisors present:

Preservation Chatter 2020

Thursday, November 19

6 — 7 PM

David Rodrigues is the Manager of Facilities and Preservation at

Preservation takes many forms and requires many hands.

Boston Preservation Alliance stands united with the voices decrying the murder of George Floyd and the long-standing history of racism this tragedy demonstrates.

The Boston Preservation Alliance offers internships to graduate and undergraduate students to help train the next generation of preservationists by providing hands-on experience in…

Let’s come together to create a wave of generosity for the organizations that help Boston thrive.

Have a preservation question? Want to hear updates about any of the preservation projects we’re monitoring?

An Environment Notification Form (ENF) has been filed with the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Office.

May is National Preservation Month which gives us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

Written by Alison Frazee, Assistant Director, Boston Preservation Alliance.

Join us for our Annual Meeting of Members

When: Postponed. New date is TBD

In light of concerns with COVID-19, we have postponed several of our upcoming events.

Is there a preservationist in your life? Or maybe you love architecture, history, and unique Boston stories as much as we do. If either of these is the case, then this is THE gift guide…

With the proposed redevelopment of the Hurley Building, we thought this is a good time…

Preservation advocates are imploring Massachusetts General Hospital to reconfigure its expansion plans to avoid demolition of three historic West End buildings, reports Dan Murphy of the…

By Isabella Labbe

August 6, 2019. Updated March 2023.

The Boston Preservation Alliance Board of Young Advisors presents:

Libations for Preservation

When:

Wednesday, July 24, 2019…

Karen McFeaters is a Boston-based painter whose work features locations around the city that highlight…

Roger Webb was the founder of the Architectural Heritage Foundation and…

Save the date for Beer + Mortar, a walking tour through Dorchester and Roxbury led by Matthew Dickey of the Alliance and HBI.…

The City of Boston invites you to a Community Meeting on the Northern Ave Bridge

Monday, June 3, 2019

Neighborhoods are living things. They evolve to the changing needs of their inhabitants. Rural farms become streetcar suburbs. Carriage lanes become roads. Thriving businesses fade.

In partnership with Massachusetts Historical Society and Fenway Alliance.

The state gets a $98M cut of GE’s sale of its property in Fort Point. Where should that money go?

May is National Preservation Month which gives us a perfect excuse to show off our beloved historic city.

Advocacy needed to OPPOSE a rule change to undercut the National Register of Historic Places

Please join us for our Annual Meeting | Registration is closed, but walk-ins welcome!

Boston Design Week Event

Boston Design Week March 27-April 7 2019

The Alliance’s Young Advisor’s Board is seeking new board members for 2019!

The Boston Preservation Alliance is now accepting nominations for our 2019 Preservation Achievement Awards!

The closing of Durgin Park (1827) following upon Jacob Wirth (1868) last year reminds us that Boston’s unique character comes from more than just architecture.

“An icon of the Boston skyline was very nearly protected against the city’s current rapacious development culture- but then the mayor stepped in.”

“An icon of the Boston skyline was very nearly protected against the city’s current rapacious development culture- but then the mayor stepped in.”

Mayor Walsh, Citgo, Related Beal (the developer of the site), and Boston University release a statement:

Mayor Walsh, Citgo, Related Beal (the developer of the site), and Boston University release a statement:

The City of Boston invites you to a

Community Meeting on the Northern Ave Bridge

The Young Advisors is a board of developing professionals whose role is to expand and amplify the Alliance’s mission of protecting places, promoting vibrancy, and preserving character.

On Monday, October 22, the Boston Preservation Alliance hosted the 2018…

Opening Remarks: Chris Scoville, Board Chair

Preservation Achievement Awards and 40 30 10 Celebration

To celebrate our 40th Anniversary year, the Alliance launched a special social media campaign: The Preservation Bucket List photo competition.

This year marks the 40th Anniversary of the Alliance, the 30th Anniversary of the Awards, and the 10th Anniversary of our Young Advisors Board.

Join the Alliance Young Advisors for a stroll through Mount Auburn Cemetery, the oldest rural cemetery in the US.

The debate over the future of the Citgo sign is still quietly grinding on.

The debate over the future of the Citgo sign is still quietly grinding on.

Boston has an estimated $20 million in annual funds to support capital projects in historic preservation, affordable housing, and parks and green spaces.

Developer Related Beal on Tuesday went before the Boston Civic Design Commission to submit its updated plans to redevelop buildings on Commonwealth Avenue near Deerfield Street.

Developer Related Beal on Tuesday went before the Boston Civic Design Commission to submit its updated plans to redevelop buildings on Commonwealth Avenue near Deerfield Street.

Developer Related Beal on Tuesday went before the Boston Civic Design Commission to submit its updated plans to redevelop buildings on Commonwealth Avenue near Deerfield Street.

Boston’s urban planners and placemakers have an opportunity to make the Northern Avenue Bridge, now a rusting relic in Fort Point Channel, a postcard-worthy destination that draws…

It has been nearly four years since anyone could walk across the old Northern Avenue Bridge, and two decades since you could drive across it.

The Boston Preservation Alliance was included in a 2018 national report regarding best practices for public outreach and education to build a knowledgeable, engaged, and activated…

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

As neighborhoods change over generations, it’s important that touchpoints to their past both remain in place and sensitively evolve to maintain their relevance.

Boston was once home to 31 breweries, enough to bestow this storied city with the title of “most breweries per capita.” A majority of the city’s breweries are clustered around…

The Boston Preservation Alliance offers internships to graduate and undergraduate students to help train the next generation of preservationists by providing hands-on experience in the…

Boston City Council voted on Thursday, June 21, to approve the first batch of Boston Community Preservation funding requests.

Boston City Council voted on Thursday, June 21, to approve the first batch of Boston Community Preservation funding requests.

You’re invited to a special preview for Alliance and Boston By Foot members. The Ladder Blocks Walking Tour will take place on Sunday, May 20, from 2:00 to 3:30 p.m.

Boston has a wonderful mix of historic buildings and sites, from stately row houses to 3-deckers, churches to commercial blocks.

The Young Advisors of the Boston Preservation Alliance are hosting a PechaKucha night on Tuesday, May 15 at The Algonquin Club of Boston.

The Alliance had an impressive showing at Preservation Massachusetts’s 30th Annual Paul & Niki Tsongas Awards Dinner held on May 9 at the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston.

May is Preservation Month. To mark the occasion, Boston Architecture Diary tapped Greg Galer to share recommendations for preservation events happening around the city.

Alliance Executive Director Greg Galer was a moderator for “Preserving Affordability, Affording Preservation,” an April 27th conference hosted by Historic New England.

The Boston Preservation Alliance is pleased to announce the appointment of Chris Scoville as a new Board Chairman and the election of Sean Geary to the Board of Directors.

The Boston Preservation Alliance is hosting its Annual Meeting on Wednesday, March 21 at historic Old South Church at Copley Square.

From old fire departments to post offices that succumbed to the demise of snail mail, buildings across the country have fallen prey to shifting markets and the rise of technology.

…

…